Introduction

It’s been ten days since I published an article on my initial solution for the IronScripter challenge Building a PowerShell Command Inventory. That solution relied on regular expressions, most commonly called regex.

The article included a primer on regex mechanics and how to use regex in PowerShell. However, the regex for each code type that I wanted to discover produced some false positives.

I asked myself, How could I get better, more accurate, code discovery?

I then remembered that, over the last few years, I have seen a smidgen of articles on PowerShell’s abstract tree syntax (AST), most notably Mike F. Robbins’ series of articles on Learning about the PowerShell Abstract Syntax Tree (AST).

General PowerShell scripters most likely would not have encountered AST in the wild. At least, not encountered and known about it.

This short article will not go into PowerShell AST; please see Mike’s articles for a deep dive. However, I will explain how I use it in my code.

Intermediate Challenge Revisited

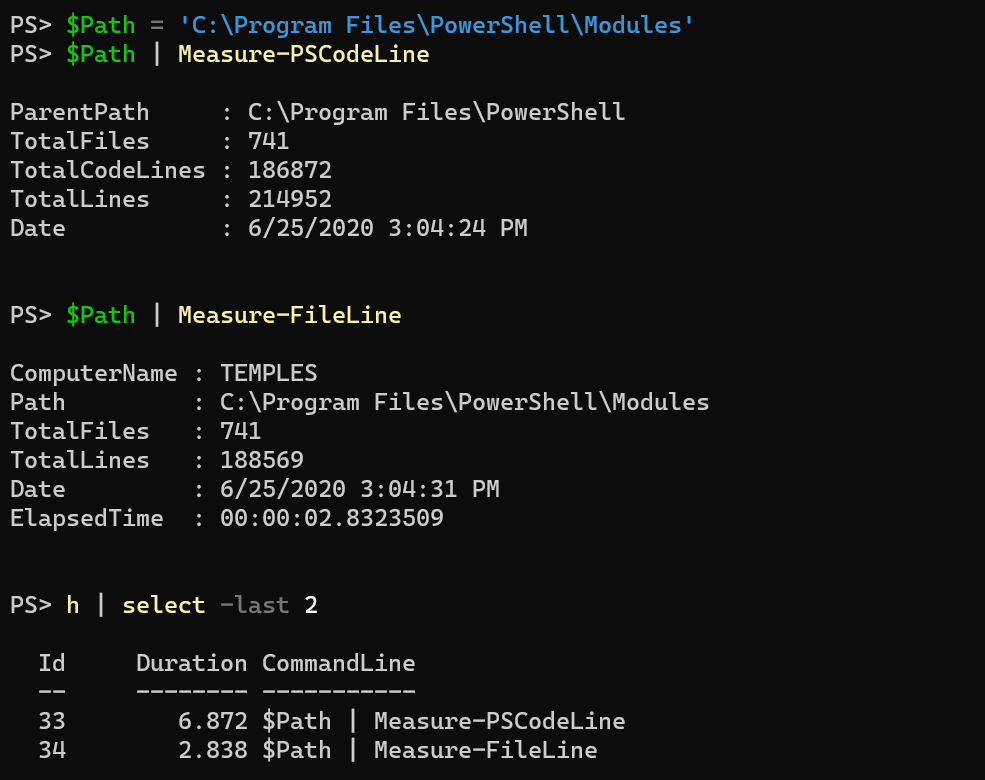

My original solution for the intermediate challenge was a function called Measure-PSCodeLine.

It iterated through each line and matched on regex \S.

This way was a bit slow.

Jeff Hicks suggested I take a look at Measure-Object, which has a parameter set for

line, word, and character count.

Using this, I updated my function and renamed it since it really isn’t tied to PowerShell files specifically.

My new function, Measure-FileLine, is much faster; just check out this improvement.

The properties in the output from both are a bit different, the main thing to focus on is TotalCodeLines in

Measure-PSCodeLine and TotalLines in Measure-FileLine.

They should be identical, and since they are not, I will err on the side of the one using Measure-Object.

Updated Intermediate Challenge Solution

Advanced Challenge Revisited

My original solution for the advanced challenge attempted to detect commands and declarations for functions, classes, variables, and more using regex.

The new-and-improved solution uses the PowerShell .Net class [System.Management.Automation.Language.Parser] and the

methods ParseFile() and ParseInput().

The former is used to read a file while the latter will parse a bare scriptblock.

Jeff’s expanded solution also uses this class and should definitely be

reviewed to see how he built the module, handled cross-platform execution, used Write-Information, and created a PowerShell class.

Parser Class

The Parser class requires two referenced variables that store output, an array of AST tokens an array of parse errors. Checking out the documentation for the Token class, we see that the class includes a TokenFlags property. This eventually leads us to the TokenFlags enum documentation where we can see that one of the fields in the bitwise enum is CommandName. Using that we can find all commands, including cmdlets, aliases, and executables.

$Tokens = $ParseErrors = $null

$null = [System.Management.Automation.Language.Parser]::ParseFile($File.FullName,[ref]$Tokens,[ref]$ParseErrors)

CommandName TokenFlag

Let’s take a look at sample Token[] output where the TokenFlags contains CommandName.

PS> $Tokens.Where{$_.TokenFlags -eq 'CommandName'} | ft -AutoSize

Value Text TokenFlags Kind HasError Extent

----- ---- ---------- ---- -------- ------

Get-Content Get-Content CommandName Generic False Get-Content

Robocopy.exe Robocopy.exe CommandName Generic False Robocopy.exe

mkdir CommandName Identifier False mkdir

Test-Path Test-Path CommandName Generic False Test-Path

Get-ChildItem Get-ChildItem CommandName Generic False Get-ChildItem

GetPowerShellCode CommandName Identifier False GetPowerShellCode

Get-CommandsFromAstTokens Get-CommandsFromAstTokens CommandName Generic False Get-CommandsFromAstTokens

Group CommandName Identifier False Group

Select CommandName Identifier False Select

Sort-Object Sort-Object CommandName Generic False Sort-Object

Get-ElapsedTimeText Get-ElapsedTimeText CommandName Generic False Get-ElapsedTimeText

Write-Information Write-Information CommandName Generic False Write-Information

We see that Kind can be Generic or Identifier. We also see that aliases could be of Identifier kind and that executables could be Generic.

I wanted to be able to include the command type, such as cmdlet, alias, filter, function, or executable. I also wanted to include the file and location where the command appeared.

Check Each Command

Each command would need to pass certain criteria.

- Does it appear in the Verb-Noun format?

- Then it should be considered a cmdlet.

- Is the command a question mark

?or two??? - If a single question mark, then it’s an alias for

Where-Object; if double, then it’s not a command.

If it fails these, then I use Get-Command to retrieve the CommandType.

For aliases, I decided to use the DisplayName property which shows the definition of the alias. This makes it easier to know where you need to look to replace the aliases in your code.

I opted to use a [hashtable] to collect all processed commands so I wouldn’t waste time going through them again.

Parameters

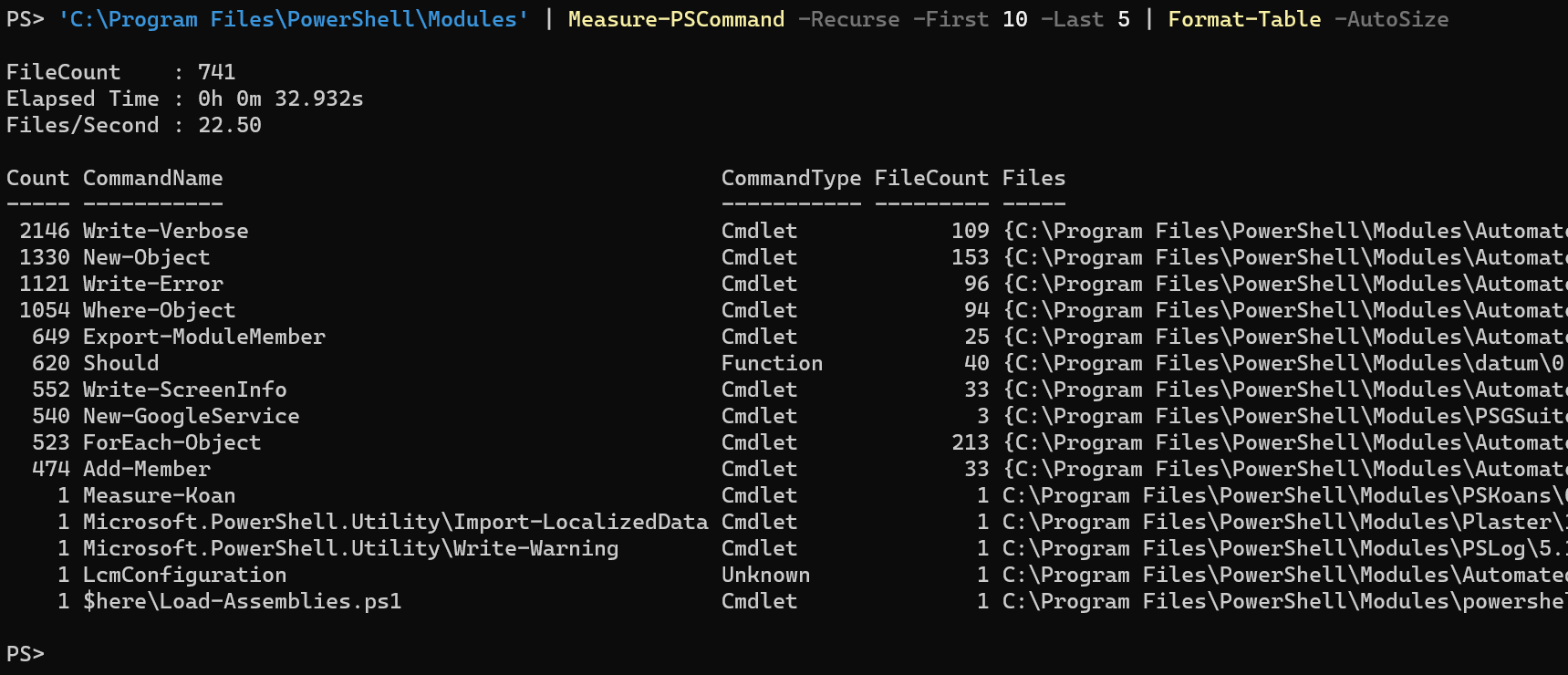

Measure-PSCommand includes Raw, First, and Last parameters.

- Raw

- Returns all commands without grouping

- First

- Used by an internal

Select-Objectto return the first n commands - Last

- Used by an internal

Select-Objectto return the last n commands

Updated Advanced Challenge Solution

Summary

As with most things in life, there is almost always more than one way to do something in PowerShell. Even when Jeff and I used the same base code, the Parser class in this case, we still took our code in different directions.

And for my two code line counting solutions, between regex and Measure-Object, I believe the latter is the best way to go.

Regardless, either way would help to bolster your skill in PowerShell.

And that is the point of the IronScripter challenges: practice, think, research, and more practice. Sacrificing just a few hours out of the month could really ramp up your PowerShell knowledge.

I encourage anyone reading this to go through the IronScripter challenges. Invest the time in your most valuable asset, you!

If you have any general questions on PowerShell, feel free to leave them in the comments or ask me on Twitter.

Thanks for reading!

Leave a comment