Introduction

The latest IronScripter challenge, Building a PowerShell Command Inventory, helps us to understand our library of PowerShell code.

It is also a good way to introduce regular expressions, most commonly called regex.

Regex and PowerShell

Before we tackle the challenge, let’s briefly discuss regex and how you can use (or probably already have used) regex in PowerShell.

What is Regex

Regex is a pattern used to match text. A regex pattern can contain letters, numbers, spaces, other characters, operators, and other constructs.

The regex engine contains categories, like characters, escape characters, character classes, anchors, grouping constructs, quantifiers, and more. This allows regex patterns to be very simple or incredibly complex.

There are numerous articles on regex and several questions on public forums. StackOverflow over 227,700 questions tagged with regex.

Note: This article will only cover a few concepts, just enough to create the solution for the challenge.

How PowerShell Uses Regex

If you’ve ever used Select-String, -match, -replace, or -split, you have used regex.

You may have used switch before, but many have realized you could use regex patterns as conditions with switch -regex.

Match Text

Consider following comparisons:

PS> 'Challenge' -match 'hall'

true

PS> 'Challenge' -match 'chall'

true

PS> 'Challenge' -cmatch 'chall'

false

In the first statement, the -match operator checks if the text hall is contained in Challenge and returns true.

The next statement also returns true because regular expressions are case-insensitive by default in PowerShell.

In the last statement, we force case sensitivity by using -cmatch.

Regex Character Classes

Regex places special meaning on some characters.

For instance, the period . is treated as a wildcard for a single character.

The backslash \ character escapes a character or is used to denote a character class.

To match on a period, you can’t use . alone; you must escape it like this: \..

Word \w, white-space \s, and digit \d are character classes that will match on a single character of the respective types.

To match on the opposite, use the uppercase, like \W for any non-word character such as white-space or punctuation.

Also, brackets can surround a character group.

To match on any character a through e, you can use the [a-e] character set.

You can also negate a character set using the caret ^ after the first bracket, such as [^abcd].

This negated character set will match on anything without the letters a, b, c, or d.

Don’t confuse this character class with a table-top roleplaying game class, such as cleric, fighter, wizard, or rogue.

Regex Quantifiers

In the previous section, you may have noticed that many of the classes match on single character. Regex has quantifiers that can be applied immediately after the class.

Here are the some common quantifiers:

*- matches the previous element zero or more times+- matches the previous element one or more times?- matches the previous element zero or one times{*n*}- matches the previous element exactly n times

Using the -Split operator, let’s examine how we can combine quantifiers with a character class for specific results.

PS> 'This is my test sentence. And this is another.' -split '\W+'

This

is

my

test

sentence

And

this

is

another

PS>

-Split returns substrings by splitting the text by \W+, or one or more non-word characters.

Spaces, or white-spaces, and periods are non-word characters.

The first sentence’s period and following space is matched with the \W+ pattern because of the +.

Here’s another simple -Split example.

PS> 'Anna ate the banana' -split 'n'

A

a ate the ba

a

a

PS> 'Anna ate the banana' -split 'n+'

A

a ate the ba

a

a

The second pattern matches on nn in Anna and it is treated as a character set to split on.

Regex Anchors and Alternation

The next two regex constructs were the first ones that I used many years ago when I supported Linux.

A regex pattern with an anchor matches when the text is in the position or grouping indicated by the anchor.

Here are the meta-character anchors:

^- match must start at the beginning of the string$- match must be at the end of the string before a newline\b- match must occur on boundary between a word character and a non-word character\B- match must not occur on a\bboundary

Alternation constructs enables either/or matching.

The most common alternation construct is the vertical bar |, sometimes called the pipeline especially in PowerShell.

You may have come across some code that looks like the following.

PS> 'The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog.' | Select-String -Pattern 'fox|dog' -AllMatches

The regex pattern will match on the words (actually each letter is matched) fox and dog.

“The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog.”

Regex Grouping

The last regex topic we need to cover before delving into the solution for the challenge is grouping.

As in math and PowerShell expression statements, parentheses, ( and ), provide the foundation for grouping.

Each sub-expression in between ( ) is captured.

The advanced solution uses named groups, which are in the form of (?<group-name>).

You can define a non-capturing group using (?: sub-expression).

Any regex specifics beyond what we’ve covered above will be addressed as the topic comes up during examination of the solution.

Intermediate Challenge

With a regex primer behind us, we can now turn to the the first challenge which asks us to count how many lines of code we have in our repertoire. Regex will play a role in the part that requires us to skip empty or blank lines.

Sample Output

D:\> $Path = 'D:\GitHub\Workshop\PowerShell'

D:\> $Path | Measure-PSCodeLine

ParentPath : D:\GitHub\Workshop

TotalFiles : 62

TotalCodeLines : 6593

TotalLines : 7620

Date : 6/13/2020 1:21:28 AM

This one was fairly simple.

I used Get-ChildItem with -Recurse to get a list of all the PowerShell files,

as designated by extensions ps1 and psm1.

Then, within a Foreach-Object loop, I read each file with Get-Content.

Next, I pipe the file contents into a Where-Object clause that performs a match on any non-whitespace characters.

In regex terms, this is a \S (uppercase S).

This gets me the non-empty or blank lines.

$CodeComments = $Content | Where-Object { $_ -match '\S' }

Lastly, I return a PSCustomObject with the required fields and counts.

By default, Get-Content will read a file line-by-line and produces an array of strings.

If you want to read the complete file as a single string object, you must include the -Raw switch.

This really useful when you are reading the contents of a JSON file, as the ConvertFrom-Json command

will only work on a string object, not the array that you get without the -Raw switch.

Advanced Challenge

The advanced challenge wants us to get a list of commands that we use in the same scripts that we just inventoried. This list of commands should be sorted by the number of times used.

For extra credit, we should be able to detect and expand aliases and, as an extra challenge, provide a array of files that contain the command.

I thought about the heart of this challenge.

Getting a command, in the Verb-Noun format, would be relatively simple with the right regex.

Discovering aliases used would be a bit harder.

But, why stop there?

Why not include CmdletBinding or Parameter attributes?

How often do you use trap or a try/catch block?

It would be nice to have a tool that parses your PowerShell code and reveals what parts of the PowerShell language you frequently use. And I wanted to have this information by file and where in the file the structure was found, namely line number and index within that line. So that’s what I built to solve the advanced challenge.

I crafted some regex patterns for each of these code constructs.

- Verb-Noun

- DotNetObjects

- -f operator

- Function

- Class

- Variable declaration

- CmdletBinding

- Parameter

- Param declaration

- DynamicParam declaration

- Try/Catch/Finally

- Trap

- Enum definition

- Loop statements

- for, foreach, do/while, do/until, while

- Switch statements

I intentionally made it easy to add additional code types. Just look at the complete function and you will see how you can add constructs by adding additional keys with regex patterns that puts the construct into a a named group.

PowerShell Code Structure Regex

The most critical regex is the one that detects a PowerShell command.

Lucky for us, a PowerShell command is in the form of Verb-Noun.

How do we make a regex pattern to match on this?

First, there can be any number of spaces before and after the command.

The verb and noun component will always be a word character, probably more than one word character per component.

And we need to handle that dash -.

Based on the previous paragraph, we can create this regex pattern: \s+(\w+\-\w+)\s+.

This should read as “any number of white-spaces before a grouping of any number of word characters followed immediately

by a literal dash then any number of word characters ending the grouping followed by any number of white-spaces”.

While this may appear to be adequate, and in another use case might be, it would be better if we named the group so we

can use the group name in cataloging the code structure.

We now have the pattern \s+(?<PSVerbNoun>\w+\-\w+)\s+ with the group name called PSVerbNoun.

In Get-PSCodeStructure, I created an ordered hashtable with each of the required code type regex pattern in sequence.

Note that the key is not important other than establishing the hashtable.

The regex patterns can be pulled from the hashtable using the $PSPatterns.Values attribute of the hashtable.

This array of values can then be concatenated using -join and the regex alternation character, the vertical bar |.

The complete, and now much more complex, regex pattern is made using $RegExPattern = $PSPatterns.Values -join '|'.

PowerShell Regex Matches

In order for our named groups to function as we need, we need something other than Select-String -AllMatches.

Also, according to the documentation, the $Matches hashtable will only contain the first occurrence of any matching pattern.

D:\> '$Variable = Get-Content -Path $Path' | select-string -pattern $RegExPattern

This only gives us the first match, $Variable = Get-Content $path.

D:\> '$Variable = Get-Content -Path $Path' | select-string -pattern $RegExPattern -AllMatches

This only gives us both matches, “$Variable = Get-Content -Path $path”, but $Matches does not have the second match.

D:\> $Matches

Name Value

---- -----

VariableDeclaration $Variable

1 $Variable =

0 $Variable =

Because of this limitation, we have to use the .Net class for [regex].

Let’s look at the class constructor overloads.

[regex]::new

OverloadDefinitions

-------------------

regex new(string pattern)

regex new(string pattern, System.Text.RegularExpressions.RegexOptions options)

regex new(string pattern, System.Text.RegularExpressions.RegexOptions options, timespan matchTimeout)

We need the string pattern and, optionally, we can supply regex options and a timeout. Unlike PowerShell, the .Net class is case sensitive, so we need to instruct it to ignore case. Note: We won’t be using the matchTimeout parameter.

The regex class has a method called Matches() which will provide us all matches.

D:\> $RegexOptions = [System.Text.RegularExpressions.RegexOptions]::IgnoreCase, [System.Text.RegularExpressions.RegexOptions]::CultureInvariant

D:\> $Regex = [regex]::new($RegExPattern,$RegexOptions)

D:\> $Regex.Matches('$Variable = Get-Content $path')

This produces the following output.

Groups : {0, 1, 2, 3…}

Success : True

Name : 0

Captures : {0}

Index : 0

Length : 11

Value : $Variable =

Groups : {0, 1, 2, 3…}

Success : True

Name : 0

Captures : {0}

Index : 11

Length : 13

Value : Get-Content

We then need to filter on the groups that matched (Success is true) and are named (Name not an integer).

D:\> $Regex.Matches('$Variable = Get-Content $path').Groups.Where{$_.Success -and $_.Name -notmatch '\d+' }

And this gives us what we ultimately needed.

Success : True

Name : VariableDeclaration

Captures : {VariableDeclaration}

Index : 0

Length : 9

Value : $Variable

Success : True

Name : PSVerbNoun

Captures : {PSVerbNoun}

Index : 12

Length : 11

Value : Get-Content

- The Name is the group name of the specific code structure type.

- The Value is the captured value from the pattern.

- The Index is the position the match was found

We use these three to build the PSCustomObject which is outputted into the pipeline.

Handling False Positives

So far, we have a regex pattern that will match on Verb-Noun.

Unfortunately, at least the way I’ve written it, this pattern will lead to false positives.

D:\> 'key. Volume-licensed systems require upgrading from a qualifying operating system.' -match '\s+(?<PSVerbNoun>\w+\-\w+)\s+'

True

D:\> $Matches

Name Value

---- -----

PSVerbNoun Volume-licensed

0 Volume-licensed

Clearly, Volume-licensed is not the name of a PowerShell command. I needed something to negate the false positives.

The method I chose was to check the Verb of the matched value with a list of approved PowerShell verbs.

$Verbs = (Get-Verb).Verb

# <truncated>

Where-Object { if ($_.Type -ne 'PSVerbNoun') { $_ } else {

if ($Verbs -contains $_.Command.Split('-')[0]) {

$_

}

}}

Important Note:

Matching on approved verbs will skip any commands that you use which do not use approved verbs.

For instance, the Encode-Sqlname and Decode-Sqlname commands from the module SqlPS would not match and, therefore,

would not be in our inventory.

Perhaps someone with greater regex-foo or a better idea on how to filter out false positives can comment below.

Capture Code Structure into Variable

D:\> $CodeInfo = $Path | Get-PSCodeStructure -Recurse

FileCount : 63

Elapsed Time : 0h 0m 13.42s

The FileCount and Elapsed Time is written to the Information Stream.

I think the Information Stream is underutilized.

It’s a great way to provide the user information and it doesn’t “clutter” up the standard output stream, like Write-Host

or Write-Output would do.

Sample Object

Let’s take a look at the first discovered code structure.

D:\> $CodeInfo[0]

FileName : BuildOnlineHelpLanding.ps1

FileFullName : D:\GitHub\Workshop\PowerShell\Functions\BuildOnlineHelpLanding.ps1

Line : 1

Index : 0

Type : FunctionDefinition

AliasName :

Command : function New-OnlineHelpLanding

We have all of the critical pieces of data we would need about this structure. We know the file, the structure type, what line contains it, where it is in the line, and the command itself.

The AliasName property will contain the alias and the Command will contain the full command name.

Important Note:

Currently, the regex pattern for detecting aliases does not discern if the alias is used within a comment.

In fact, none of the regex can discern if the code type is used within a comment.

Again, perhaps someone with greater regex-foo or a better idea on how to filter out false positives can comment below.

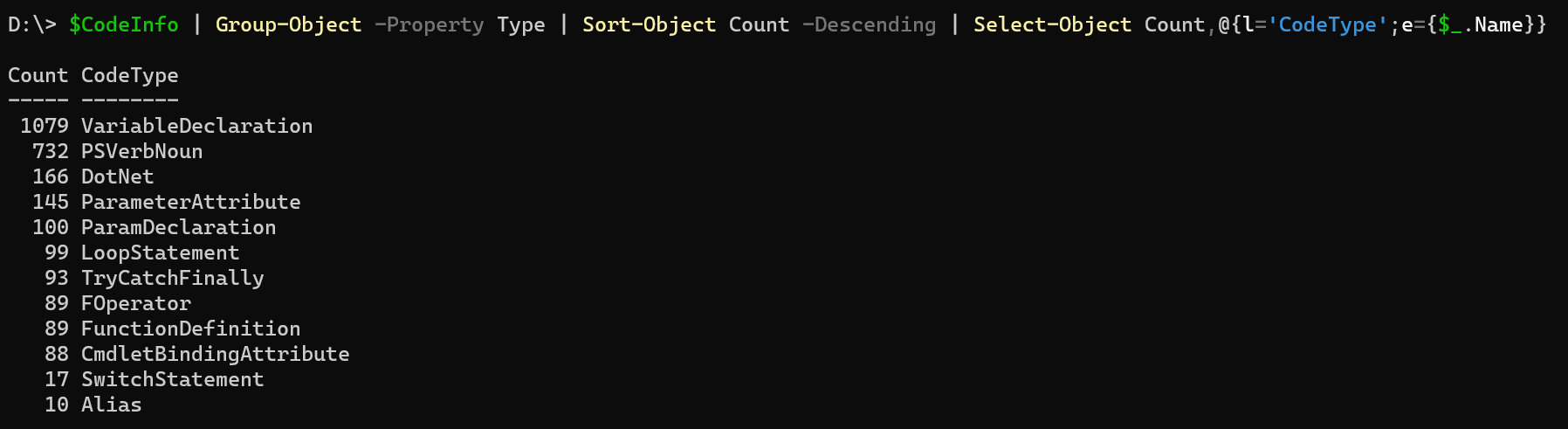

Count of Structure Types

We can use Group-Object to get a count of the code structure types.

Throw in Sort-Object and Select-Object

D:\> $CodeInfo | Group-Object -Property Type | Sort-Object Count -Descending |

Select-Object Count,@{l='CodeType';e={$_.Name}}

Count CodeType

----- --------

1079 VariableDeclaration

732 PSVerbNoun

166 DotNet

145 ParameterAttribute

100 ParamDeclaration

99 LoopStatement

93 TryCatchFinally

89 FOperator

89 FunctionDefinition

88 CmdletBindingAttribute

17 SwitchStatement

10 Alias

Looks like I need to go back and remove some Aliases.

Count of Verb-Noun Commands and Aliases

D:\> $CodeInfo | Where-Object {$_.Type -match 'PSVerbNoun|Alias'} |

Group-Object -Property Type | Sort-Object Count -Descending |

Select-Object Count,@{l='CodeType';e={$_.Name}}

Count CodeType

----- --------

732 PSVerbNoun

10 Alias

This shows that I have 732 PowerShell commands in the scripts within this folder. These may include commands in comments.

Advanced Extra Credit Challenge

From the list above, we can also see that I have used 10 aliases. Let’s check those out and how I pulled those out of the code.

D:\> $CodeInfo | Where-Object {$_.Type -match 'Alias'} | Format-Table -AutoSize

FileName FileFullName Line Index Type AliasName Command

-------- ------------ ---- ----- ---- --------- -------

New-EventFilterXml.ps1 D:\GitHub\Workshop\PowerShell\Functions\New-EventFilterXml.ps1 141 54 Alias select Select-Object

New-EventFilterXml.ps1 D:\GitHub\Workshop\PowerShell\Functions\New-EventFilterXml.ps1 149 54 Alias select Select-Object

Write-PlasterParameter.ps1 D:\GitHub\Workshop\PowerShell\Functions\Write-PlasterParameter.ps1 109 117 Alias select Select-Object

build.settings.ps1 D:\GitHub\Workshop\PowerShell\PlasterTemplate\build.settings.ps1 101 6 Alias Select Select-Object

PingViewer.ps1 D:\GitHub\Workshop\PowerShell\Scripts\PingViewer.ps1 420 341 Alias Select Select-Object

temp.ps1 D:\GitHub\Workshop\PowerShell\Scripts\temp.ps1 20 8 Alias ForEach Foreach-Object

temp.ps1 D:\GitHub\Workshop\PowerShell\Scripts\temp.ps1 66 17 Alias Select Select-Object

temp.ps1 D:\GitHub\Workshop\PowerShell\Scripts\temp.ps1 86 18 Alias ForEach Foreach-Object

temp.ps1 D:\GitHub\Workshop\PowerShell\Scripts\temp.ps1 93 28 Alias Select Select-Object

temp.ps1 D:\GitHub\Workshop\PowerShell\Scripts\temp.ps1 94 25 Alias Select Select-Object

In the begin block of Get-PSCodeStructure, you will find $Aliases = Get-Alias.

After the regex patterns have gathered any matches, I split the line and start iterating through each ‘word’.

Since foreach and select are also part of Verb-Noun commands, I first attempt to match on them specifically.

Next, I attempt to match the ‘word’ against all the names in $Aliases and if the ‘word’ contains only letter.

Advanced Extra Challenge

As an extra challenge, we were asked to include a property that is an array of the filenames where the command exists.

Lucky for us, the FileName is tucked away in the Group property.

D:\> $CodeInfo | Where-Object {$_.Type -match 'PSVerbNoun|Alias'} |

Group-Object -Property Type | Sort-Object Count -Descending |

Select-Object Count,@{l='CodeType';e={$_.Name}},@{l='FileName';e={$_.Group.FileName}}

Count CodeType FileName

----- -------- --------

732 PSVerbNoun {Add-ModuleUnitTests.ps1, Add-ModuleUnitTests.ps1, Add-ModuleUnitTests.ps1, Add-ModuleUnitTests.ps1…}

10 Alias {New-EventFilterXml.ps1, New-EventFilterXml.ps1, Write-PlasterParameter.ps1, build.settings.ps1…}

Solution

Here are the two functions I wrote to solve this challenge.

Performance

One consideration in processing a numerous files is performance.

I tested using PowerShell 7’s Foreach-Object -Parallel and a standard foreach statement on a folder path containing

157 files.

Here are the results.

| Iteration | Foreach-Object -Parallel | foreach |

|---|---|---|

| Run 1 | 0h 0m 24.223s | 0h 0m 25.638s |

| Run 2 | 0h 0m 25.4s | 0h 0m 19.659s |

| Run 3 | 0h 0m 29.780s | 0h 0m 27.159s |

There’s not that much difference between the elapsed time.

However, I did notice that Foreach-Object -Parallel consumed more processor and memory, using up to 450MB and up to 80% CPU.

The foreach statement only consumed up to 150MB and up to 25%.

Based on these findings, I chose to use the foreach statement only.

Other Notes

For the Advanced challenge, we need to pass a path.

I wanted to provide the user a way to supply a single file or a path.

If provided a path, any ps1 or psm1 files would be selected.

I also provided a -Recurse switch that allows the user to select all multiple downstream paths.

With this criteria in mind, here’s how I did that.

$PathType = (Get-Item -Path $Path).GetType().Name

if ($PathType -eq 'DirectoryInfo') {

if ($PSBoundParameters.ContainsKey('Recurse')) {

$Files = Get-ChildItem -Path $Path -Recurse -File |

Where-Object { $_.Extension -in $PSCodeExtensions }

} else {

$Files = Get-ChildItem -Path $Path -File |

Where-Object { $_.Extension -in $PSCodeExtensions }

}

} elseif ($PathType -eq 'FileInfo') {

$Files = Get-ChildItem -Path $Path

}

Additional Information

To learn more about regex, here are a few resources that go much deeper into the topic than this article.

- Powershell: The many ways to use regex on Kevin Marquette’s blog

- A Practical Guide for Using Regex in PowerShell on Josh Duffney’s blog

- About Regular Expressions

- .Net Quick Reference on Regular Expression Language

I’m not a regex guru.

For several years now, I have crafted my regex using the following online validator tools. There are others, these are just the ones I find familiar and easy to use.

Summary

Thank you for sticking with the article! I didn’t realize that it was going to grow this large, to a 15+ minute read time.

When I began working on this Iron Scripter challenge, I was only considering writing a short article on my solution. I quickly realized, however, that the heart of the challenge involves regular expressions. And I suspect that many PowerShell scripters would only have a little experience or knowledge on this complex subject.

My hopes for this article are twofold:

- You have gained a better understanding of regex and how you can use and write regex patterns in PowerShell.

- You have gained an interest in participating in the Iron Scripter challenges, or have had your interest bolstered. You can learn a great deal while solving the challenges.

If you have suggestions for better regex patterns or a better way to handle false positives for Verb-Noun and aliases, please let me know in the comments below.

If you have any general questions on Regex or PowerShell, feel free to leave them in the comments or ask me on Twitter.

Leave a comment